Overview

Threat modeling works to identify, communicate, and understand threats and mitigations within the context of protecting something of value.

A threat model is a structured representation of all the information that affects the security of an application. In essence, it is a view of the application and its environment through the lens of security.

Threat modeling can be applied to a wide range of things, including software, applications, systems, networks, distributed systems, Internet of Things (IoT) devices, and business processes.

A threat model typically includes:

Description of the subject to be modeled

Assumptions that can be checked or challenged in the future as the threat landscape changes

Potential threats to the system

Actions that can be taken to mitigate each threat

A way of validating the model and threats, and verification of success of actions taken

Threat modeling is a process for capturing, organizing, and analyzing all of this information. Applied to software, it enables informed decision-making about application security risks. In addition to producing a model, typical threat modeling efforts also produce a prioritized list of security improvements to the concept, requirements, design, or implementation of an application.

In 2020 a group of threat modeling practitioners, researchers and authors got together to write the Threat Modeling Manifesto in order to “…share a distilled version of our collective threat modeling knowledge in a way that should inform, educate, and inspire other practitioners to adopt threat modeling as well as improve security and privacy during development”. The Manifesto contains values and principles connected to the practice and adoption of Threat Modeling, as well as identified patterns and anti-patterns to facilitate it.

Four Questions

Adam Shostack first introduced the Four Questions in his book, Threat Modeling: Designing for Security, and it has since been adopted by many organizations as well as serves as the foundation for Threat Modeling Manifesto.

What are we working on?

The first step is defining what you’re working on. For example, you might choose to model:

What you’re working on this sprint or improvement

Software or applications

Enterprise architecture

Operational technology

Mobile apps

Internet of Things (IoT)

When you decide what you’re working on, you also start to build models. Diagrams are models of what you’re working on. A lot of people confuse form and function here. What’s important is creating data- and process-flow diagrams that help you share what’s in your head with the people around you.

Specifics

Identify use cases, scenarios, and assets - An essential part of threat modeling and reviewing threat models is understanding what business functions or “use cases” the system has. Scenarios describing the sequence of steps for typical interactions with the system illustrate its intended purposes and workflows. They also describe the different roles of users and external systems that connect to it. The first step in threat modeling is to document the business functions the system performs and how users or other systems interact with it. Supplement textual descriptions of use cases and scenarios with flowcharts and UML sequence diagrams as needed. Whether you use formal documentation such as use cases and scenarios, or take a more informal approach, ensure you provide context that answers these questions:

What are the business functions of the system?

What are the roles of the actors that interact with it?

What kind of data does the system process and store?

Are there special business or legal requirements that impact security?

How many users and how much data is the system expected to handle?

What are the real-world consequences if the system fails to provide confidentiality, integrity, or availability of the data and services it handles?

An asset is something of value in a system that needs to be protected. Some assets are obvious such as money in financial transactions or secrets such as passwords and crypto keys. Others are more intangible like privacy, reputation, or system availability. Once you properly identify the system’s assets, it is easier to identify threats against them. Document the list of system assets.

Examples of tangible assets:

Personal photos and contacts stored on a smartphone

Compute resources in a cloud environment

Software supply chain integrity in a development environment

Medical imaging and diagnostic data

Financial accounting data

Biometric authentication data

Proprietary formulae and manufacturing processes

Military and government secrets

Machine learning models and training data

Credit card data

Examples of intangible assets:

Customer trust

User privacy

System availability

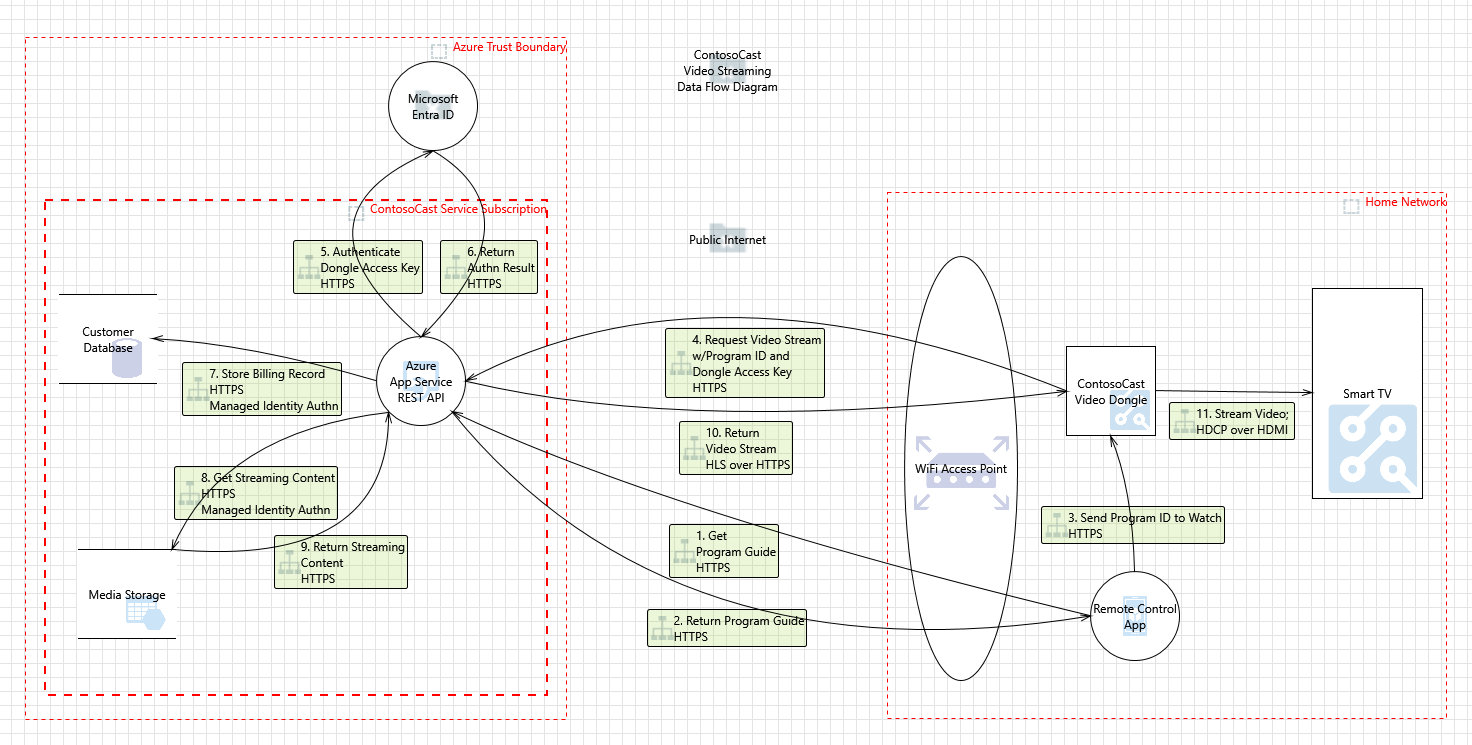

Create an architecture overview - In addition to documenting business functionality and assets, create diagrams and tables to depict the architecture of your application, including subsystems, trust boundaries, and data flows between actors and components. At minimum, a Data Flow Diagram (DFD) is recommended, and other supplementary diagrams such as UML Sequence Diagrams to illustrate complex flows may also be helpful. A DFD is a high-level way to visualize data flows between the major components of a system. It is a simplified view that does not include every detail—just enough to understand the security properties and attack surface of the system. It is a recommended practice to label the following in your DFD arrows:

Data types (business function)

Data transfer protocols

A trust boundary is a logical construct used to demarcate areas of the system with different levels of trust such as:

Public Internet vs. private network

Service APIs

Separate operating system processes

Virtual machines

User vs. kernel memory space

Containers

Trust boundaries are important to consider when threat modeling because calls that cross them often need to be authenticated and authorized. Data that crosses a trust boundary may need to be treated as untrusted and validated or blocked from flowing altogether. There may be business/regulatory rules related to trust boundaries. For example, sovereign clouds must ensure that data is stored only within their trust boundaries, and in some cases, HIPAA Protected Health Information (PHI) shouldn’t cross trust boundaries. Trust boundaries are often illustrated in DFDs with dashed red lines.

What can go wrong?

Once you know what you’re working on, you can start thinking about all the different things that can go wrong. If you’re a glass-half-empty person, this is where you’ll shine. The glass-half full folks will creatively brainstorm.

Some considerations include:

Who’s the intended user?

What’s the intended use?

Can an unintended user get access to it?

Can someone use it in an unintended way?

Specifics

Identify the threats – Threat modeling is most effective when performed by a group of people familiar with the system architecture and business functions who are prepared to think like attackers. Here are some tips for scheduling an effective threat modeling session:

Prepare the list of use cases/scenarios and, if possible, a first draft of DFDs in advance.

Limit the scope of your threat modeling activity primarily to the system or features that you are developing or directly interface with.

Designate an official notetaker to capture and record threats, mitigations and action items during the meeting.

Reserve at least 2 hours for the meeting. The first hour will usually be spent on getting a common understanding of system architecture and what scenarios you are modeling so you can spend the second hour identifying threats and mitigations.

If you can’t cover it all in two hours, decompose the system into smaller chunks and threat model them separately.

Invite people of varied backgrounds, including:

Engineers who are developing and testing the system

Product owners who can weigh security risk against business goals

Security analysts/engineers

People who are proficient at software testing (violating system assumptions, testing boundary conditions, generating invalid input, etc.)

STRIDE is a common methodology for enumerating potential security threats that fall into these categories:

Category |

Definition |

|---|---|

Spoofing |

Making false identity claims |

Tampering |

Unauthorized data modification |

Repudiation |

Performing actions and then denying that you did |

Information Disclosure |

Leaking sensitive data to unauthorized parties |

Denial of Service |

Crashing or overloading a system to impact its availability |

Elevation of Privilege |

Manipulating a system to gain unauthorized privileges |

People and threat modeling tools apply this methodology by considering all the elements in a dataflow diagram and asking if threats in any of the STRIDE categories apply to them. STRIDE is useful for novice threat modelers who have not been exposed to all these threat categories and so might miss some important threats. However, STRIDE is not a substitute for thinking like an attacker. STRIDE may miss important design flaws that only thinking like an attacker will catch.

Thinking like an attacker is the most important and difficult part of threat modeling. Once you and your team understand the system architecture, use scenarios, and assets you need to protect, you must imagine what could go wrong with your system if a motivated, capable attacker attempts to compromise it. Thinking like an attacker is not as simple as applying a methodology like STRIDE to enumerate threats. You must also challenge the security assumptions in your design and contemplate what-if scenarios in which some or all your security controls fail as attackers actively try to compromise your assets. Examples of security assumptions:

We assume our open-source dependencies don’t have malicious code.

We assume that cloud computing services are inherently trustworthy.

We assume that app users will not root their mobile devices.

We assume that all authenticated users have benign intent.

Validate that your security assumptions are correct and consider what happens if they are not. Determine if any assumptions are invalid based on the threat landscape and the value of the assets you need to protect. It helps to study historical incidents to gain insight into the attacker mindset.

Many threats and mitigations are highly technical, and you are unlikely to think of them all on your own. Educate yourself on threats and associated mitigation techniques that apply to the domain you are working in. For instance, every web developer should be aware of attacks like cross-site scripting (XSS), cross-site request forgery (CSRF), and command injection. Study resources like the CWE Top 25 Most Dangerous Software Weaknesses and the OWASP Top Ten to learn more.

Record the threats you identify in your engineering team’s work tracking system and rate their security severity so they can be prioritized accordingly. Document the threats you identify with sufficient detail that those reading them later can understand them. Well-written threats clearly describe:

The threat actor who exploits the vulnerability

Any preconditions required for exploitation

What the threat actor does

The consequences for affected assets and users

What are we going to do?

The question “what can go wrong” helps you figure out the threats. When you look at what you’re going to do, you address each threat.

Some types of actions include:

Mitigating threats: Make it harder for someone to take advantage of a threat.

Eliminating threats: Remove the feature or interface that creates the threat.

Transferring threats: Have someone else be responsible, like having a customer change default settings.

Accepting threats: Recognize that the time and effort to mitigate or eliminate the threat undermines the purpose of the project.

While these sound like, and are aligned to, risk management strategies, they are subtly different. Remember: threats are the things that can go wrong. Risk management focuses on the likelihood and impact of threats. You can use implicit agreement when choosing because it can be faster and easier than formal risk management approaches.

Specifics

Identify and track mitigations - Secure Design Philosophy: When identifying mitigations, keep in mind that security is not “all or nothing”. A partial mitigation that raises the cost for an attacker, slows them down to give defenders time to detect them, or limits the scope of damage is much better than no mitigation at all. Think in terms of layered defenses. Attackers don’t just exploit a single vulnerability and stop there. They chain multiple vulnerabilities together, pivoting from one target system to the next until they achieve their objective (or get caught.) Each layered defense increases the likelihood that attackers will be blocked or detected. Also, assume that other layers’ security controls will be bypassed or disabled. This is the essence of the Assume Breach philosophy which results in a resilient set of layered defenses rather than relying solely on external defenses that, if bypassed, result in a major breach.

Recommended Secure Design Practices:

Design and Threat Model as a Team

Prefer Platform Security to Custom Code

Secure Configuration is the Default

Never Trust Data from the Client

Assume Breach

Enforce Least Privilege

Minimize Blast Radius

Minimize Attack Surface

Consider Abuse Cases

Monitor and Alert on Security Events

Threat modeling is not complete until you create work items to track your threat findings and the related development and testing tasks to mitigate them. Consider tagging the work items and writing queries so they are easy to find. A threat model provides the seeds for a good security test plan. Be sure to test that your mitigations work as intended and use automated testing when possible.

Did we do a good job?

Finally, you need to validate your threat model by checking your work to make sure it’s as complete as possible.

This step includes checking:

The model: make sure it matches what you built, starting with the diagram.

Each threat: review that you found all the possible threats and did the right thing with them.

Tests: ensure you have a good test to detect the problem, one that is in line with other software tests and the risks that failures expose.

Additional Resources

Guides and Trainings

Microsoft: Threat Modeling Security Fundamentals

Adam Shostack: Worlds Shortest Threat Modeling Course

ShellSharks: A Threat Modeling Field Guide

OWASP: Threat Modeling Process

Tools

See [TM TOOLS](TM TOOLS.md)